Some Famous Tibetan Doctors

Prof. Barshee Wangyal

Memories of Dharamsala – Dr Pasang Yonten Arya

PROFESSOR BARSHEE PHUNSTOK WANGYAL (1914 -1983)

A Tribute on the centenary anniversary of his birth

At 18 years old, all that I knew about Dharamsala was that it was the seat in exile of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the emanation of Awaloketeshvara, and so to my mind, it had to be situated on a vast plain, with a great palace surrounded by his Bodhisattva ministers, like a kingdom in paradise. On the bus, these grand expectations had given way to the stark realities of narrow, winding, bumpy roads through mountainous terrain, until finally reaching the lower Dharamsala market environs and Forsyth Ganj and then Mcleod Ganj, I had seen Tibetans among the local Indians as we drove through the small village.

It was still winter and cold enough so that our breath turned into clouds of vapor as we disembarked from the bus at the small bus stand at our destination, the second Lhasa, in India. All around was covered in a thin blanket of snow, including the branches of trees that bent towards the earth under the weight. I was struck by the quiet of the white surroundings, and of the bright sun rays in a clear blue sky overhead.

It was some days later before I received a call from the Gowo Lobsang Tenzin, my ex-teacher, with instructions on where to meet with the other students. Gowo Lobsang Tenzin was a tall, strong monk with a powerful, no-nonsense demeanor. He gave a short introduction before distributing the Tibetan Medicine Tantra Book, soap, towel, and other items. We were around fifteen students in all, divided into three groups and allocated to three wooden houses. The living conditions were poor, but we were uplifted with the joy and happiness of being there and determined to dedicate ourselves to the studies that lay ahead. This determination overcame any doubts or shortcomings of our surroundings. The senior medical students and Men-Tsee-Khang staff were very kind and made us feel welcome.

Days passed and our Medicine and Astrology Professor still had not shown up to start our class. I did not feel worried or anxious to see the master because in my heart I knew he would eventually come, and that this was the place I would stay and grow up through him. My mind was firmly made up and nothing could shake this resolve. Maybe I was naïve, coming from Nepal’s Mountain School, but I felt very peaceful and tranquil, with no doubts at all in my heart. It was similar to a monk who leaves the house of his parents and goes for refuge in the forest without attachment. There was no regret and no attachment left in me! I still remember my mother saying to me, when I was so excited to go to medical school in India:

“Mother’s heart is to the son, but son’s heart is like stone”.

Those words still pain me even though I am much older now.

At night I would read the medical Tantra book and explain it to friends. One morning a senior student asked me whether I had already studied medicine because of the authority I used when explaining. He was surprised to learn that it was the first time I had read the medical book. I was not surprised or proud. In retrospect, I can say that from the beginning, the medical Tantra was somehow very familiar to me, and therefore I had no trouble at all studying or committing things to memory.

We took our meals on the verandah of the old Men-Tsee-Khang wooden house in McLeod Ganj, seated according to seniority. I remember vividly the delicious Tibetan tea and bread taken on that verandah. Passersby would see us doing the medicine Buddha sutra, rite and rituals there on that verandah, and they as well as patients and other people would make prayer requests.

A few days passed before the director, Ven. Lobsang Tenzin brought Professor Barshee Phuntsok Wangyal to the small wooden classroom to introduce him to the class. He was a tall, fair skinned gentleman with a serene, beautiful face and white teeth, his salt and pepper hair was combed neatly from the left to the right side. He was wearing a thin white shirt with a dark blue jacket and trousers. I noticed that he had long, beautiful fingers and that he wore a red ruby on his ring finger. I also noticed that he had some white rice grains clinging to the hair around the top of his head. I was later to understand that this marked him as a learned devotee of the wisdom Goddess Saraswati, uncommon to find in the Tibetan community, and that he was an expert in poetry and Sanskrit Saraswati Grammer (dbyang can sgra mdo).

I spent the next nine years learning important lessons from Professor Barshee. During that time I witnessed his constancy in his daily devotional practice, and how it extended to everything around him, so that he liked to have clean surroundings, clean clothes, poetry, flowers and music. His smiling countenance mirrored a deep peace and tranquility within, and he found joy everywhere. He loved talking to children, innocent people and of course, with learned scholars. He especially loved the spring and summer months. During the summer he would don a thin white shirt and dark blue trousers and under the shade of a tree, with a fresh breeze blowing, he would play his flute, or simply sit gazing through his Tibetan sunglasses down into the valley, or talk with students. Wherever he was invited to go, even to official or students picnics, he would carry along his flute. He loved the feel of new paper money notes before they lost their sheen, music, teaching, the history and biographies of many masters, and especially his lifelong study in Buddhist philosophy and practice in Jangchub Lamdon (Atisha Dipamkara’s lamp of the path) and Lama Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim chenmo (stages of the path) and Bodhicharyavatara practices (Bodhisattva’s path and practice). He melted into, and embodied the poetry, philosophy, grammar and astrology that he taught to his students. At the same time he was strict about maintaining the traditional style of teaching discipline. He was a precious storehouse of literary scholarship with traditional Indo-Tibetan Sanskrit grammar knowledge. He also knew Tibetan traditional Dhel Tsee (rdel rtsis) arithmetic calculation, and had great love for astrology sciences. Many of these sciences he taught to the Men-Tsee-Khang students and also to western scholars.

Without exaggeration, it was as if the Goddess of Saraswati was dwelling in his heart and blessing his every moment, so he experienced the whole world in a poetry-filled, dream-like state. Therefore, even his intellectual and daily teaching activities were completed in a dream-like state of deep contemplation. His memory was incredibly sharp, strong and powerful. He could remember all the dialects, body gestures, modes of speaking and costumes from the different parts of Tibet. His mind was like a video camera that recorded and saved all events. Once he heard and paid attention, he never forgot.

He was extremely careful in his study and practice and passed on very important things to help us with our childish natures. One day, all of us students went to Thekchen Choeling to receive initiation from His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The next day in class, smiling, he asked:

“Do you know what Tantric initiation means?”

He continued: “It is like a snake that enters a Bamboo tube. There are only two gates, either you go up to the pure land or fall down in Vajra hell. It is very dangerous and there is much samaya or commitment that you should keep like your life. But never mind, in case you even fall down there, after sixteen lives, Yidam (chosen deity) will rescue you anyway”. He went on to say, “I don’t have such courage to make it, I practice sutra and there is no danger of falling down, but can go up slowly. I received only Kriya Tantra initiation and no more than that. More higher means you should keep more samaya the commitments”.

One of the most important lessons he gave to guide us in practice was:

“You should receive teachings from the master and respect that the master is like Buddha who passes the Buddha’s teachings to you. Then go away and stay a distance from the master’s place. Study what you have learnt and put it into practice. If you have a problem of understanding or practice, you may come and ask for the teachings and solve the problems. The reason is that because our five senses are imperfect and mind is not well trained, we may see, hear, smell, and understand wrongly the master when we remain in close proximity to him. Master has no problem but our eye fails always. Taking sun light is better at a distance than near to the sun.” Then he would go on to tell us many stories of monk police, managers of Monasteries and secretaries of Lamas, among others.

Professor Banshee would quote from Sakya Pandita’s Ethic and Moral discipline and then follow with:

“What is the purpose of all these ethical and moral disciplines that occupy your mind if you are not able to tame and control your mind?”

His teachings were of great value, they nourished our mind and body and gave us an essence and a meaning of life. I remember that one day I was his assistant to bring him to the Tibetan Dialect School for teaching. We stopped at one Restaurant in Mcleod Ganj whose owner was the cook in Sikkim School, where our master was superintendent. The Restaurant was famous for Tibetan Momo food, but tiny and not that clean. He ordered tea and reminisced with the owner about the Sikkim school. All the while, he covered his teacup with his hands to protect it from flies, but he still said, “Your tea is best among the teas that I ever remember”. I was in the corner and thought to myself, “master does not care whether or not there are flies”.

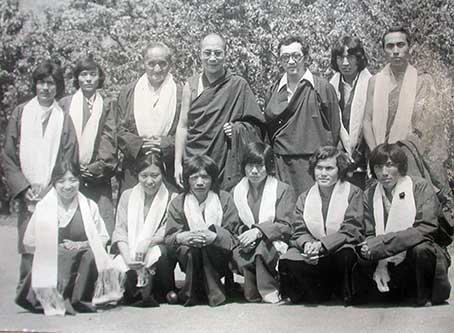

In 1977, our group graduated in medicine and astrology and had an audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. I remember that His Holiness said, “You can believe that the world is wide open for you to pursue your endeavours”.

In 1982, I was in the fifth year of Tibetan Pharmacology specialization offered by Men-Tsee-Khang after my graduation (traditionally the post is offered only to the top graduated students), with my friend Namgyal Tsering. I was among the group of people who was preparing “Gnulchu Tsotru Chenmo” (great mercury purification work and precious pills). The team was led by Dr. Tenzin Choedrak, the personal physician to His Holiness, and the work was performed in the back garden of the residence of His Holiness, in Dharamsala. It was a great time for my advanced study of Tibetan Pharmacology and alchemical works.

During these special great mercury purification days, one day I was called by Mr. Lobsang Samten the elder brother of His Holiness, who was the director of Men-Tsee-Khang. He told me that Professor Barshee needed an assistant teacher, one to whom he could pass on the tradition, and that he had chosen me: “From tomorrow you should go to the Medical College as an assistant and take up the responsibilities that Professor Barshee is going to give to you.” I was surprised at the unexpectedness of this request, but I accepted right away. Then I went to see Professor Barshee, who said, “…you should help in my work, especially the new comer’s courses. I need rest and have many other things to do.” I said, “I shall happily accept the work under your guidance if you see me as a suitable candidate.” From that day I worked with him until he passed away.

I recollect that he told us some of his life story. He was the only son to his parents who were part of a noble family called Drongshar in Shang county, in the upper part of Tibet. His other house was called Barshee, in Lhasa, where one of the family members was expected to enter the service of the Tibetan Government. From childhood, he had a traditional Tibetan education. His father dreamt that he would be a powerful and influential man in Tibetan Government like his uncle Kuchar Chikyab Khenpo, a powerful monk who was the personal secretary to the 13th Dalai Lama, and so increase the standing of the family in the society. Unfortunately, he was not interested in Government and politics but instead ran away to Tashilunpo Monastery, where he began to study Buddhist philosophy. There he met Kachen Kyilkhor Rimpoche, Kachen Zopa Rimpoche, Kachen Pemala and many others. There with the monks he entered the world of philosophical debate and programs of study. His father however, intended to keep him at home, so he dutifully got married, but often ran away from home to continue his studies at Tashilunpo. His wife was a gentle, wise woman, the niece of Ngagchen Dharpa Rimpoche, the ninth Panchen Lama’s right hand high Lama, and he said that it was from him that he received the medicine Buddha initiation. He took care of his family while studying deeply and widely subjects including: Tibetan Buddhist sutra, Philosophy, Medicine, three systems of astrology, Tibetan and Sanskrit Grammars, poetry, graphics, painting, music, even western medicine pharmacy practice. He learned the Tibetan medicine from Chuwar Amchi in his county but Gyud-shi from Dakpo Tenzin the senior student and doctor of Lhasa Men-Tsee-Khang.

When he was 32 years old he became sick from hypertension and mental instability due to working extremely hard studying and searching for the truth of emptiness. It is likely that he underwent treatment and a number of different therapies that did not work, until finally he went to see spiritual master Ven. Shri Gyal gyi Chusang Rimpoche (reincarnation is now in Kathmandu, Nepal), from whom he said he received many teachings and especially he received “Maning Hadhon” practice, and cured his psychological disharmony. From that time until he was 39 years old, he stayed at home and rested, while helping patients with free medications. He also invited Lamas, scholars, village elders, spirit porters (person who serves as porter to the spirits), and many others, listened to legends, stories, Tibetan demonology or ancient Tibetan spirits legends, learned names of mountains, rivers, Indian mythology and cosmology, painted house, made medicines and visited patients to name a few. Gradually, he become a storehouse of legends, esoteric stories, demons and spirit stories, especially about Samye Monastery and spirit temple among others, and the development of ancient Tibetan people and their clan, race and ethnic groups and names. Professor Barshee would forget all about time whenever he recounted stories from this period of his life.

In 1959, when the Chinese occupied Tibet, Dr. Barshee was 45 years old. He suffered greatly in that particular situation and fled to Sikkim in India where he got a job as a Schoolteacher, later becoming superintendent. While he was there in Sikkim he was poisoned by a jealous teacher. The modern medicine treatments he received all failed. Fortunately, a friend of the family recognized that he had been poisoned, which was the reason the medicines had not worked, and that he needed local poison treatment. The wife brought some green leaves and chopped them to make a paste which she mixed with milk and let him drink. After the first day he began to vomit and have diarrhea, and then health came back, he said.

When he was 54 years old, in 1968, he came to Dharamsala by order of His Holiness, and a year later he started work as a Professor in Men-Tsee-Khang. Under his tutelage four batches of Tibetan doctors graduated. He made yearly horoscopes for His Holiness, as well as having other important private consultations.

In 1973, when we first met in Dharamsala at Men-Tsee-Khang Medicine school he was 59 years old, and later, when I served as a junior teacher training under his guidance in Tibetan medical college in 1982, he was 68 years old. At this time, although Dharamsala was a tiny hill station in Indian Himalaya and isolated from the rest of the world, news of his knowledge and willingness to teach spread to India, Nepal, Bhutan and even to the west. Numbers of students, scholars and interested people began to gather there, increasingly from every corner of Asia and the west. Generally, they came from monasteries, Tibetan Government-in exile staff members, individuals from India, Nepal, and foreigners from abroad. He also taught at Varanasi Tibetan higher study, Tibetan dialectic school at Dharamsala and other places. Professor Barshee became a model layman scholar, specialist in traditional Tibetan sciences and philosopher to many young Tibetans. All his private teachings were free to any person who came to him, whether monk or lay.

The latter part of his life was mainly spent in reciting Mantra, meditation and merging with his Sadhanas. He never told us what he was doing, but we know that he practiced Bodhicharyavatara, Langri Thangpa’s eight verses of mind training. He received many teachings from His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and he would often go to Kyabje Ling Rimpoche and Kyabje Trijang Rimpoche for discussions on Sanskrit Grammar and Philosophy. He received teachings from Namgyal Monastery Khan Rimpoche (Gaden rgyabo la), Ghen Pema Gyaltsen and Ghen Nyima la (Shakor khan Rimpoche) from Drepung Loseling monastery, and especially sought after Khunu lama Rimpoche Tenpe Gyaltsen and Khunu lama Tenzin Gyatso for Bodhicharyavatara.

To my knowledge, he has composed several books on Tibetan Grammar, a Book on Poetry, Supplement booklet to Pulse and urine diagnosis (phyi rgyud rtsa chu’i lhan thabs), Bodhicaryavatara’s new commentary (blo bzang dgongs rgyan) etc. There are number of unpublished small works and valuable notes on medicine, astrology, philosophy and practices etc.

One day in 1983, Professor Barshee had stomach complaints and it began to swell. Tibetan medicine and western medicine treatment helped little. According to Barshee Tsedon Ngawang Tenkyong’s work on his father’s biography, his father was fine and went in to the Tibetan dialect school as usual. While there, he ate a meal of Tibetan Thukpa (Tibetan noodles), and went home with stomach complaints. He said that this was the cause of his father’s death.

During this period when he was sick in bed, we were the second group of his students to see him. Following the tradition, we requested him to extend his wish to live longer life. Then he told us his dream. He said, “According to my dream this time I will not recover from this illness.” The dream is, he said, “I was in front of this house and taking sunshine while standing against the wall. It is like after noon and looking toward the west. Suddenly from the western horizontal sky of Tibetan Children’s village side, an eagle came in my direction and it threw a thin white thread which stuck at my ring finger. Then the eagle went away again to the west.” Then he said, “This means my time is now coming to an end”, and he gave us some advice. After a few days he passed away and we all made his final funeral. His wife divided some of his precious books with us and some are still with me in my collections for memory.

We were extremely fortunate to have such a very special human being as our teacher. He was an honest man who always spoke the truth, and was a great lay Buddhist practitioner. He had the ability to look at things and understand it all in a positive way. He was a man of books and learning, who dedicated his whole life to the search for study and practice. I think there are some more memories in my mind but this is a piece of my time with the master who is now in Sukhavati (bdeva can) the Western pure land.

To commemorate the centenary anniversary of Professor Barshee’s birth, it would be fitting if we, his students, from all over the world, honor his legacy by remembering the blessings of his teachings and feeling his presence in our hearts.

Pasang Y. Arya

04.04.2014